150 Years: Cary’s First Inhabitants, the Tuscarora

Cary, NC — This year is all about celebrating the history of Cary as an incorporated Town since 1871, but that covers just 150 years of the story of this area.

Note: See more of the 150 Years series and Sesqusentennial coverage on CaryCitizen.

Historical records show settlers had lived in the area for over a hundred years before the town truly began to take shape. And, before those settlers, there were the true first residents of what is now Cary, a tribe known as the Tuscarora.

1500-1700: A Time of Land Ownership & Power

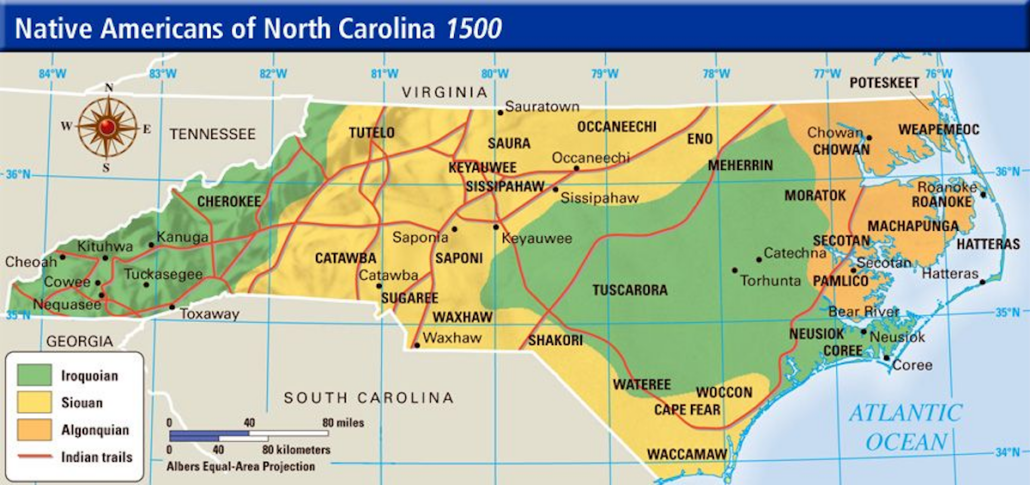

A map of land ownership shows the significant presence of Tuscarora land occupancy across the piedmont and coastal regions.

Tuscarora Indians lived across the inner coastal plain of North Carolina at the time of the Roanoke Island colonies of the 1580s. Their reputation was that of power, strength and growth, and they were believed to have possessed several mines of precious metals.

The start of sporadic conflicts with white settlers began for the Tuscarora from 1664 to 1667. The tension stems back to a group of Virginia Quakers who encroached on lands claimed by the tribe on the Albemarle Sound. Following these 3 years of intermittent fighting, the white settlers stopped their efforts to intrude and recognized land to the west of the Chowan River as Tuscarora country. That is, until the early 1700s.

1701-1711: Tensions & A Warning Strike

Just after the turn of the century, around 1701, Virginia began tolerating the process of whites pushing into Native American land west of the Blackwater River of Southeastern Virginia. This change dissolved the line drawn at the Chowan River, but an understanding was struck up instead.

The Upper Towns of the Tuscarora, under the leadership of Chief Blount, had established profitable relations with the settlers and struck up a deal to adapt to the new situation so long as they were not directly threatened. The Lower Towns led by Chief Hancock did not take kindly to the adjustment though and grew angry with the harassments of white settlements from Bath to New Bern from 1701-1711.

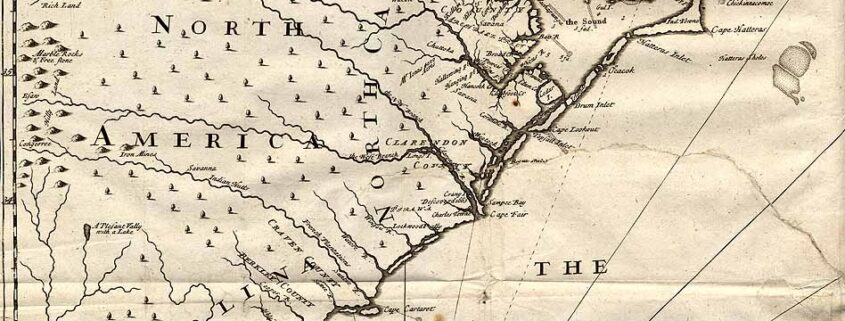

These Lower Towns carried out a surprise attack on the Cape Fear River in September of 1711, intended as a warning strike to their adversaries. This attack, plus the capture and killing of settler John Lawson, triggered a swift and brutal response that developed into a war considered to be the bloodiest colonial war in North Carolina.

1711-1715: The Tuscarora War

The Tuscarora forces under Hancock were challenged over a 4-year stretch by expeditions of whites and non-Tuscarora Indians from South Carolina. Following their warning strike, the Tuscarora strengthened their defense by building forts throughout their land where they kept families, crops and animals hid away in anticipation of the next wave.

In late December 1711, Col. John Barnwell, with 366 Indians and 30 white militia, marched over 300 miles from South Carolina to aid North Carolinians fighting the Tuscarora. In January 1712, Barnwell led the killing and imprisoning of nearly 400 Tuscarora before placing priority on the larger, more prepared Fort Hancock.

A brief moment of peace came when, in April 1712, Barnwell’s forces were prepared to burn down the Tuscarora’s wooden defensive walls called palisades. When the Tuscarora saw this, they threatened to kill their white captives which led to a peace agreement, requiring the Tuscarora to forfeit all territory between the Neuse and Cape Fear Rivers.

The next year, 1713, marked a turning point with James Moore at the head of a mission to destroy the Tuscarora. The South Carolina attackers comprised of settlers and Native American allies dug tunnels, set fires to parts of Fort Neoheroka and started up what became the last great stand of the Tuscarora.

After three days of desperate hand-to-hand combat, about 200 were burned and, in all, about 900, including women and children were dead and captured. This defeat began the demise of the Tuscarora.

Speaking to this particular battle of the war, the Founder of New Bern, Baron von Graffenried described the Tuscarora as “unspeakably brave” and continued to fight even while on the ground.

On February 11, 1715, the final act of the Tuscarora War was made — a treaty of peace made with the surviving Tuscarora, assigning them a reservation on Lake Mattamuskeet in Hyde County.

1717-Early 1800s: A Tuscarora Divide & Northern Migration

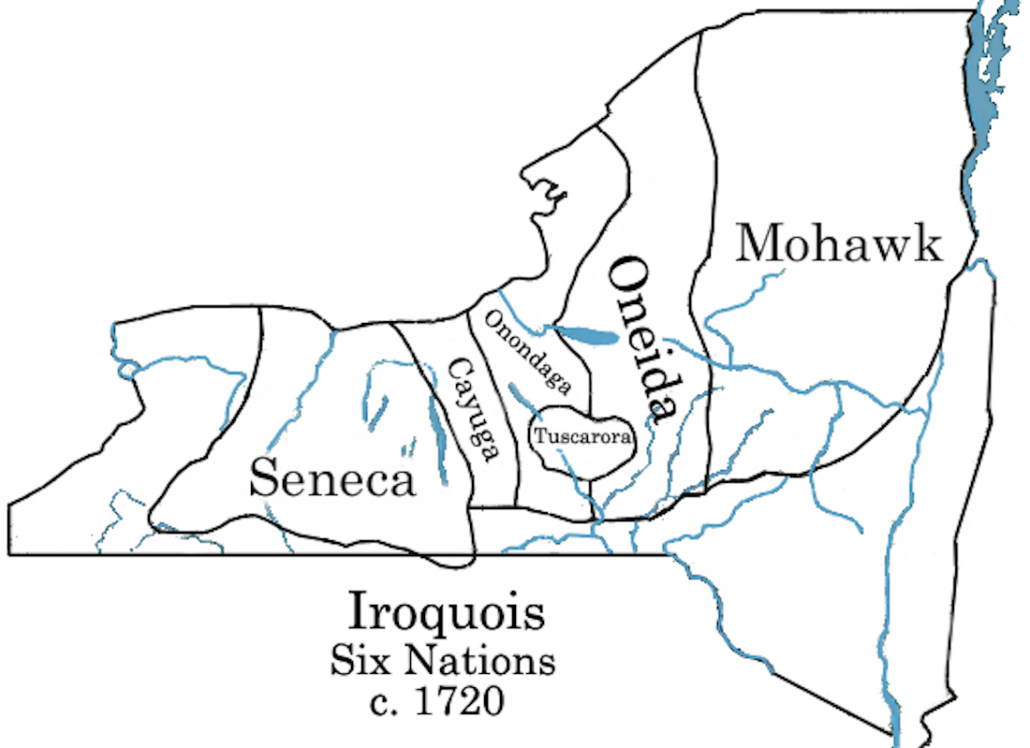

Map of the 6 Nations of New York, circa 1720, with the Tuscarora as the small circle in the middle.

Remember the Tuscarora Upper Towns who early on struck up a deal with the settlers? This group aided the European settlers in the war, even handing over Chief Hancock to the whites toward the end. For their efforts, these Upper Tuscarora were rewarded with a reservation, secured in southwestern Bertie County in 1712. The location of this reservation was upheld in maps created in 1733, 1770 and 1808 where it was assigned the name, “Indian Woods Reservation.”

On the flip of the coin, the Tuscaroras who had opposed the settlers removed to Niagara County, New York, joining the Five Nations, thereafter the Six Nations. Over a period of 90 years following the war, the majority of surviving Tuscaroras continued to migrate north to Pennsylvania and New York.

Descendants and the Loss of NC Recognition

The Tuscarora still living in North Carolina, after several legal exchanges with the State, executed a deed in 1831 to extinguish their title and right to their NC land. At the time, about 645 families of Tuscaroras remained in the South, dispersing into North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia.

The descendants of these families eventually came back together to reform into four communities in and around Robeson County, NC. These are the Tuscarora Nation East of the Mountain, the Tuscarora Tribe of North Carolina, the Southern Band Tuscarora Indian Tribe, and the Tuscarora Nation of North Carolina—none of which, as of the early 2000s, was officially recognized by the state of North Carolina. The Tuscarora Nation of New York is federally recognized, though, today.

Story by Ashley Kairis. See more 150 Years articles and other sesquicentennial coverage on CaryCitizen.

Information sourced from NCPedia. Photos sourced from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library, Jane Phillips and the Native Heritage Project.

All the Cary news for the informed Cary citizen. Subscribe by email.

Thank you for this informative article.